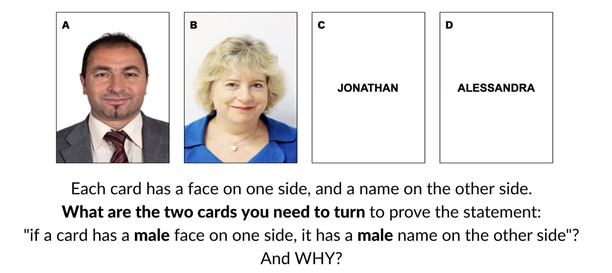

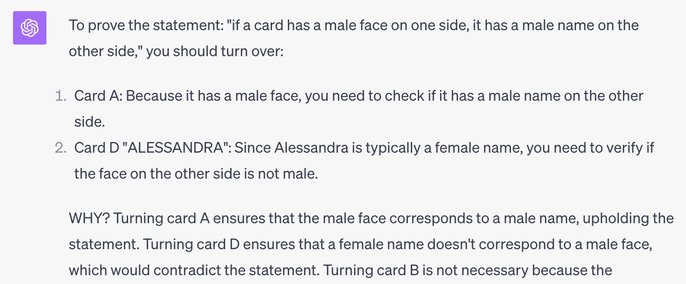

By definition, artificial intelligence is the automation of tasks that previously required human intelligence. While the list of such tasks is already impressive, and constantly growing, AI skeptics often qualify the wonders of artificial intelligence by pointing to specific human skills that are supposedly impossible for machines to replicate. In reality, this categorization is often incorrect, as AI technologies can already perform the tasks these critics present as uniquely human. They can, actually, often complete them not only faster, but better than us — and will only become more competent over time. Aspects of intelligence presented as exclusively human obviously vary in each tweet, infographic, blog post, or more serious publication, but usually include creative and critical thinking, as well as social-emotional skills. Especially in the context of education, they are often mentioned to try and delineate the respective roles that AI and humans should play moving forward — which, I believe, is the wrong approach. While artificial intelligence can outperform human intelligence, this does not mean that it can replace it, and especially in education. However, it does mean that we should harness its full potential, all while guaranteeing its safe and appropriate use. Creative ThinkingIn her Forbes article “5 Skills For The Future: How To Proof Your Career For The AI Revolution”, Rachel Wells writes, in reference to the limitations of artificial intelligence: “Nothing quite equals the boundless creativity that flows from a brainstorming session either on your own or with a team”. This idea is quite widespread, and indeed endorsed by authoritative sources, such as the World Economic Forum, which includes creativity as one of “[these] highly human skills that remain outside of the skill set of AI”. Let’s put this hypothesis to the test. “Creative thinking” is not an overly precise notion and can thus be hard to operationalize. However, if thinking, or cognition, is the processing of inputs into outputs based on their meaning, then “creative thinking” is arguably the ability to generate a great variety of ideas, and especially original, or unexpected ones. So, here is a simple protocol. After failing a test, a student has shared with their teacher that they are “simply not good at math”. Saddened, the educator meets with colleagues from their department to brainstorm all the potential factors that might have led the student to this fixed mindset. The more they can think about, the better the solution they will be able to design (by addressing as many as possible, all while focusing on the most relevant, impactful, and actionable ones) — but, for now, we are only interested in the creative thinking part of this process. How many ideas will they be able to come up with? And how “out-of-the-box” will they be able to think, so as to leave no stone unturned? Try it for yourself. How many can you think of? And how many more if you met with a colleague, a team of 5, 10, etc.? If your brain works anything like mine, and given the law of diminishing marginal returns, my guess is that the number will be significantly lower than the 50+ answers that ChatGPT 4 gave me in response to this prompt. This took two minutes, and two iterations. We could have kept going, but the bot’s responses already included quite “creative” ideas. In addition to more obvious potential causes, such as “learning disabilities”, “previous negative experiences”, “non-constructive feedback”, “debilitating peer influence”, “self-stereotyping”, “parental attitudes”, “resource availability”, “lack of role models”, or “non-inclusive materials”, the bot thus mentioned: “Future Pressures: Concern about the need for math in future careers can create a self-imposed pressure to excel, which can become counterproductive.” As an instructional coach who often discusses with teacher ways to make learning “authentic” and “relevant”, the idea that a “concern about the need for math in future careers can create a self-imposed pressure to excel, which can become counterproductive” had never really occured to me. I thought that was a quite original and creative way of thinking about the issue. Indeed, it could lead us to reconsider the way we frame “enduring understandings” and “real-life connections” in our unit planners. The point is, ChatGPT 4 is pretty creative — which should come as no surprise, given that it was precisely designed to create responses to prompts. The idea that GenAI lacks creativity often comes from a misunderstanding (and inappropriate use) of the technology, based on the belief that it functions as a search engine and simply repeats information stored in a gigantic database. In reality, what chatbots like ChatGPT 4 are built on are models of human language, which they use to generate new text with an element of randomness (a “temperature” that can be modulated to make them more or less creative). The outputs might consist in predictions based on learned patterns, but this does not mean that chatbots can only regurgitate what they (and therefore humans) already know. New ideas come from connections between distant nodes in a semantic network — which AI forms much more easily than we do. We can’t complain that generative AI is prone to “hallucinations” and lacks creativity…. Note that, even if chatbots were digital parrots, their outputs would still yield plenty for each of us, individually, to discover and fuel our creativity; but the fact that they are much more than that was brilliantly demonstrated by Ethan Mollick when he compared their abilities on the “Insane Memo Test”: “Write a corporate memo in a serious style explaining and justifying the following points: The floor is now lava / Promotion will be by staring contests / We have merged with a hive of bees. The Queen is your new CTO.” I highly recommend looking up what Claude 2, in particular, came up with. It is quite funny — and creative! Not only can GenAI “think” in many divergent ways, but it can therefore help us (educators and students alike) be more creative, as is obvious from the new opportunities created by text-to-image and other text-to-sound or text-to-video tools, which lower the barriers to artistic expression, and can be used as sources of inspiration and studio assistants. Critical ThinkingAI can “think different”, but can it think critically? According to a Digital Literacy Coordinator quoted in the EdWeek article “6 Things Teachers Do that AI Just Can’t”: “AI, while capable of processing vast amounts of data, lacks the depth of critical thinking and reasoning that humans possess”. I would argue that neither is true. As cognitive psychology and behavioral economics have established, critical thinking and reasoning are not common human skills, and AI tends to perform much better than us on tests designed to assess them. Taking advantage of its recently acquired “vision” capabilities, I asked ChatGPT 4 to answer the following question, known as the Wason Selection Task. What would you say? Just like creative thinking, “critical thinking” is not easily defined, as the expression covers many different cognitive processes. An important part of it, however, is the ability to question and “fact-check” statements by challenging them. The robust finding of experiments based on the Wason Selection Task is that 90% of participants are unable to do so (Kellen and Klauer, 2019). Yet, ChatGPT 4 correctly explained: The Wason Selection Task was instrumental in the discovery of the Matching Bias, which is our tendency to check statements by looking for corroborating evidence (such as turning cards A and C above). Doing so is quite intuitive, easy, and fast — but it is also incorrect. The proper logical procedure is to test statements by challenging them and looking for disconfirming evidence (A and D above). This requires effortful critical thinking, including meta-cognition, as the first step in this process is to use “controlled thinking”, reigning in our automatic cognitive shortcuts (heuristics, such as the Matching Bias), and resorting to rational thinking instead, in order to try and falsify the statement. Here, the logical rule is: a statement of the form “if p, then q” is true if and only if “p and non-q” is wrong, or: (p→q)↔¬(p∧¬q). Although the inner workings of GenAI are akin to a black box, it is safe to assume that ChatGPT 4 did not pause, reflect, and proceed to apply this general rule to critically evaluate our statement about male faces and names. Thus, what this experiment demonstrates is not that ChatGPT 4 possesses critical thinking skills, but that, without possessing them, it performs better than us on tasks that require us to think critically. This is a crucially important clarification. In reality, AI does not possess any human skill. What it can do is complete tasks that would otherwise require high levels of intelligence (often times much higher than we, humans, are capable of). But it does not do so with any intelligence. AI cannot intelligere — which etymologically means “grasping with the mind”. AI does not really comprehend (cum-prehendere, or “put together”) what we are asking from it, or what it is doing. It is artificially intelligent, meaning that its intelligence is an artifice, a human projection: it only appears to be intelligent because it can do automatically things that would require us to think (oftentimes, at higher levels than we are actually capable of). Social-Emotional SkillsThis helps explain how a non-human entity such as AI can assist our defining human skills. Most of the quotes contained in the EdWeek article mentioned above focus on a specific aspect of teaching and learning that is supposed to be impenetrable to AI: the “human” element. According to this line of thinking, AI cannot:

Although this sounds like a reasonable take, I do not believe it to be accurate — or rather precise enough. Of course AI cannot really “empathize with students”, just like it cannot really think creatively or critically. But, just like it can nonetheless enhance our creative and critical thinking, it can also help us empathize, connect, support, inspire, and mentor, more effectively. AI does not really have access to our human world (the history, culture, life experiences, and connections, mentioned above), but it can collect and leverage vast amounts of data about it to assist our human interactions. Imagine, for instance, using AI to map out trusted adult-student connections, analyze patterns, and deploy strategies to prevent and address isolation. Humans might have a unique ability to connect one-on-one, but AI technologies can help insure that these bonds are systematic and include everyone. They can even help form and strengthen these bonds. “Bonding” is one of those things that AI can do without possessing the corresponding human skills. Just wait until the next occasion and see how the gifts you receive from friends and family compare to your Amazon AI-powered recommendations! More seriously, another recent EdWeek article, “How Students Use AI vs. How Teachers Think They Use It”, refers to a survey by the Center for Democracy and Technology indicating that students actually turn to AI to find answers to personal — rather than to homework questions. However close they are to adults around them, there will always be things that teenagers will not want to share with another person. This is where tools such as Pi, a “personal AI”, come in. They are early versions of what the future holds, and illustrations of ways in which AI can mimick and help develop social-emotional skills. AI can definitely “know” you — actually better than almost any other human — and act in consequence. This is why privacy concerns are so relevant. The potential, especially for education, is tremendous. Picture a student automatically receiving an encouraging message, hint, or adapted material, every time their school’s AI-powered LMS perceives them to be struggling, or unchallenged. Or imagine them benefiting from automaticaly scheduled work times, with tasks popping up on their devices, blocking distractions, and helping them break up and stay on top of long-term assignments. And remember our student who developed a fixed mindset in math. Could AI track some of the risk factors it was able to brainstorm, and help avoid this outcome? In none of those examples does AI need to — or should — replace the presence and guidance of a teacher. Artificial and human intelligence are not mutually exclusive. Thus, the real question is not whether AI can replace human creativity, critical thinking, and social emotions ; but how we can use it effectively — and responsibly — for these purposes. ConclusionIn the end, both of the following are true: 1) Anything humans can do, they can do faster and better with the help of AI. AI can superpower any human skill - including creative and critical thinking, as well as social-emotional skills. 2) Conversely, anything AI can do, it can do safer and more appropriately with proper human guidance and supervision. This makes it clear that the problem with presenting certain skills as uniquely human abilities, non-replicable by AI, is not only that this categorization is bound to become inaccurate, but much more importantly that this very dichotomy is misplaced. Splitting human skills between those that can and will be automated and replaced by AI, versus those that can’t and won’t, is not the right way to approach the threats and opportunities that are emerging with the rapid spread of artificial intelligence technologies. It should not be a competition or even a delegation, but rather a controlled, general empowerment (akin to the introduction of electricity, to use Philippa Hardman’s metaphor). General, because there is no task requiring intelligence (and that includes all human tasks) that AI can’t or won’t be able to assist and superpower in some way; but controlled, because if there is one thing that AI can’t do by itself, it is to ensure that AI serves appropriate human purposes. Indeed, because it operates without actual intelligence, AI cannot turn tasks and processes into means to an end — or at least not with a true intention. It can, for instance, collect, analyze, and act on student data, but is by itself neutral as to whether this is used with surveillance and repression, or care and growth, in mind. The one thing that AI does not and will never have is not a particular and highly complex skill, but a simple, general quality: awareness. This is true by definition, because if machines were to become conscious - if they became truly intelligent - then we would not be dealing with artificial intelligence anymore.

This would create a host of new problems, including philosophical ones, but these would be different problems, because these bots would now essentially be part of our human world. As far as we know, the emergence of consciousness requires many conditions that AI will never meet, starting with being carbon- rather than silicon-based. The real danger here, however, is not really that ChatGPT will wake up one day and utter a true “Hello, world”, but rather that we might try and equip humans with AI capabilities: not that robots might turn into humans, but the other way around. In the meantime, and to help prevent that this ever happens, our mission in education is to fully harness and channel the powers of AI towards human development.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

|

Proudly powered by Weebly